When you have an animal named after one of the seven deadly sins, a common question is which came first, the animal or the sin? Geologically speaking, the credit goes to the animal, as the sloth lineage existed long before there were humans to give it any name.

Image of Georges Cuvier in 1795, the year before he described Megatherium.

While the native peoples of South America had given names to both the living three-toed and two-toed tree sloths – as the Ai for the former and the Unaü for the latter – very few people are familiar with these names unless they are a crossword puzzle aficionado. So where does this animal having been named after one of the seven cardinal sins come in? In the fourth century, Evagrius Ponticus, a Christian monk, wrote a paper entitled “Eight Evil Thoughts,” which he listed as gluttony, lust, avarice, anger, sloth, sadness, vainglory, and pride. The list was later shortened to seven in 590 AD by Pope Gregory I (ca. 540 – 604 AD) which in Latin are Superbia, Avaritia, Luxuria, Invidia, Gula, Ira, and Acedia. For English speakers, the common name, sloth, originated in the 12th century as a translation of the Latin word acedia. In Latin, it means sluggishness or indolence and was used to replace the Old English ‘slæwð’ and ‘slǣwth’ and was the basis of the Middle English words slowe and slou. In the romance languages such as Spanish, it is ‘perezoso,’ or in French, ‘paresse,’ both also mean lazy while in German it is ‘faultier’ or lazy animal, and even in the Tupí language, ‘unaü’ means lazy, so the poor animal is stereotyped no matter what language you speak.

So, while the word sloth has been around for quite a while, its application as the name of an animal did not come until later with the discovery of the New World and its many new types of animals by European explorers. Sloths, both living and fossil, are members of a

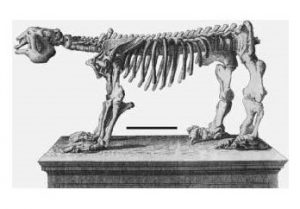

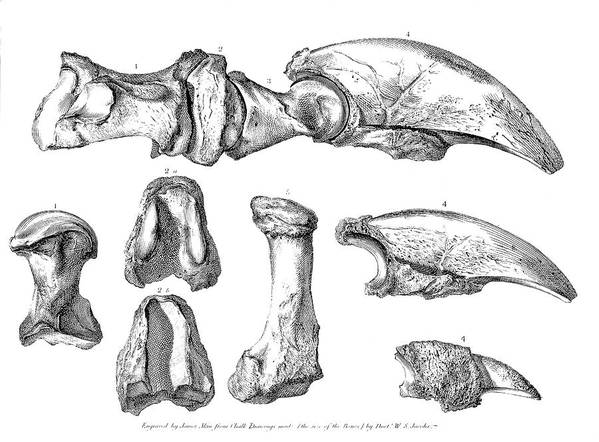

Drawing of Megatherium americanum by Juan Bautista Bru de Ramón in 1793, and first published by G. Cuvier in his description of the animal in 1796.

group of mammals that originated in South America and later dispersed into Central and North America along with a few islands in the Caribbean. We do not know which European explorer was the first to see a living tree sloth or even bring a specimen back to Europe, but the first description and illustration of a sloth were by Konrad Gessner (1516 – 1565), a Swiss physician, naturalist, bibliographer, and philologist. One of his major works, Historia animalium, published between 1551 and 1558, included for the first-time descriptions of many of the new animals that had been discovered by European explorers. The sloth was included in Volume 1: Live-bearing four-footed animals (1551). As there were no close relatives to sloths present in the Old World, Gessner had nothing with which he could compare the sloth, and was presumably only working from the skin of a dead animal. Not having seen a live animal, the description and habits he provided do not do the animal justice. He did note that the sloth lived in trees, so decided it was a type of monkey and gave it the name Arctopithecus – which means bear-ape – and illustrated the animal standing with all four feet on the ground.

Unfortunately, sloths did not fare any better under Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) in his 10th edition of Systema Naturae published in 1758 in which he recognized eight major groups

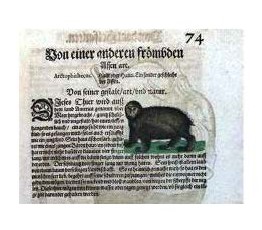

Konrad Gessner’s entry of the sloth from volume 1 of Historiae animalium, published in 1551

of mammals. By this time, the two living sloths had been placed in the genus Bradypus (slow foot), each as a distinct species with the descriptive names of didactylous (two-toed) and tridactylous (three-toed). While sloths were at least no longer considered to be primates (monkeys and apes), they were instead included in the Bruta which, as defined by Linneaus, were mammals that had tusks instead of fore-teeth, feet with strong hoof-like nails, moved slowly, and ate mostly masticated vegetables. Along with the sloth, other members of the Bruta included the Asian elephant, the West Indian manatee, the Chinese pangolin, and all three of the living anteaters, the silky (pygmy), the collared anteater or tamandua, and the giant anteater. Today, we do know that the South American anteaters, or vermilingua (worm tongue), are closely related to sloths, but their other close relatives, the armadillos, were placed in the Bestiae, a group with an indefinite number of fore-teeth on the sides, always one extra canine, and an elongated nose used to dig out juicy roots and vermin. Along with armadillos, the Bestiae included a diversity of animals that today are not considered closely related including pigs, hedgehogs, moles, shrews, and opossums.

Georges Cuvier (1769-1832), the French naturalist and zoologist, is considered instrumental in establishing the fields of comparative anatomy and paleontology through his work in comparing living animals with fossils. In 1817, he used the similarity in the anatomy of the feeding structures to propose a relationship between echidnas, anteaters, armadillos, pangolins, and aardvarks, as well as platypuses and sloths, and placed them in a new group called Edentata (animals without teeth). Today, we recognize that Cuvier’s Edentata included four modern mammalian orders that represent at least five separate radiations of ant and/or termite-feeding specialists, and the similarities seen in these ant and termite eaters are independently derived and are the result of convergent evolution. Because the group Edentata originally included such a diverse group of mammals, the sloths, anteaters, armadillos, and their extinct relatives are now placed in the order Xenarthra (meaning strange joint) based on many unique characters in both the skeleton and soft anatomy not seen in any other mammals, including the extra pairs of articulations in the vertebrae of the lower back that gives the group its name.

Alonso de Ojeda (ca.1466 – ca. 1515) was the commander of the fleet which included Juan de la Cosa and Amerigo Vespucci that is credited with the discovery of South America and as the first European to visit Guyana, Curaçao, Colombia, and Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela in 1499. Despite the extensive colonization of South America by the Spanish and Portuguese, it was not until nearly 300 years later, in 1788 that the first fossil sloth was discovered. The skeleton was found on the banks of the Luján River in what is today Argentina. But at that time the region not only included Argentina, but also Paraguay, Bolivia, and Uruguay and was officially named the Virreinato del Río de la Plata, or the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata. The fossil bones were sent to Spain the following year and presented to the King for inclusion in the Royal Cabinet (now the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales) in Madrid. The bones were cleaned and reassembled as a mounted skeleton by museum employee Juan Bautista Bru (1740–1799).

While the skeletons of modern animals had been mounted for many years, this was the first time a fossil skeleton had been mounted on an iron framework in a standing pose. Bru also drew the skeleton as well as some of the individual bones. While the details are not known, copies of Bru’s drawings were smuggled out of Spain and sent to Georges Cuvier in France. As Cuvier had access to an extensive and diverse comparative collection, he was able to determine the

Konrad Gessner’s entry of the sloth from volume 1 of Historiae animalium, published in 1551relationships and appearance of the animal and determined it was a giant sloth, as the skeleton of the animal is comparable to elephants in size. He published his first paper on the animal in 1796 based on a

transcript of a lecture he had previously given at the French Academy of Sciences. In this paper, he gave it the name Megatherium americanum (great beast of the Americas). This also made Megatherium the first fossil vertebrate to be given a formal name using the Linnean system. Cuvier again published on the sloth in 1804 and included this paper in his book, Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes. The description of Megatherium set the stage for the recognition of the other types of extinct sloths that were subsequently discovered not only in South America but in North America as well, along with Central America and on several islands in the Caribbean. Eventually, additional skeletons of Megatherium were discovered and sent to other museums such as the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle in Paris, the Natural History Museum in London, and the Field Museum in Chicago. The Museum of Natural History in Paris obtained its skeleton of Megatherium from Tarija, Bolivia in 1854, 22 years after the death of Cuvier, so it appears he probably never saw any original bones of the animal he named.

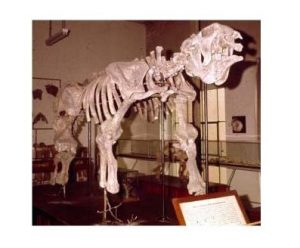

The skeleton of Megatherium americanum, the first mounted skeleton of a fossil animal on exhibit at the National Museum of Natural History in Madrid, Spain.

This blog is brought to you by Dr. Greg McDonald, a retired vertebrate paleontologists but a very active Research Associate with The Mammoth Site.

Additional blogs and future exhibits at The Mammoth Site will feature more interesting information about these strange Ice Age mammals – many that are researched right here at our institution. Did you know that ground sloths are now known from the fossil record in South Dakota? More to come!

Lang Family Dig Building Dedicated

HOT SPRINGS, S.D. – Donations and support from local...

Mammoth Site Awarded Re-Accreditation from the American Alliance of Museums

For Immediate Release Release Date: July 14, 2023...

International Beaver Day

Kelly Lubbers, Bonebed Paleontologist Happy...

A Bone Voyage

“I have been wonderfully lucky, with fossil bones — some of the animals must have been of great dimensions: I am almost sure that many of them are quite new; this is always pleasant, but with the antediluvian animals it is doubly so.” —Letter from Charles Darwin to his sister Caroline, October 1832.

Botany and Bones in Brazil

By Greg McDonald The first discoveries of the ground...

The American Pronghorn and its Ancient Relatives

Richard S. White, Research Associate Antilocapra...

Saltpeter and Sloths

It was not long after Cuvier described the first...

Mammoth Site Researchers Involved In Discovery of New Capybara Fossil Species

HOT SPRINGS, S.D. – Researchers from The Mammoth Site...

Proboscideans from US National Park Service Lands

Jim I. Mead, Justin S. Tweet, Vincent L. Santucci,...

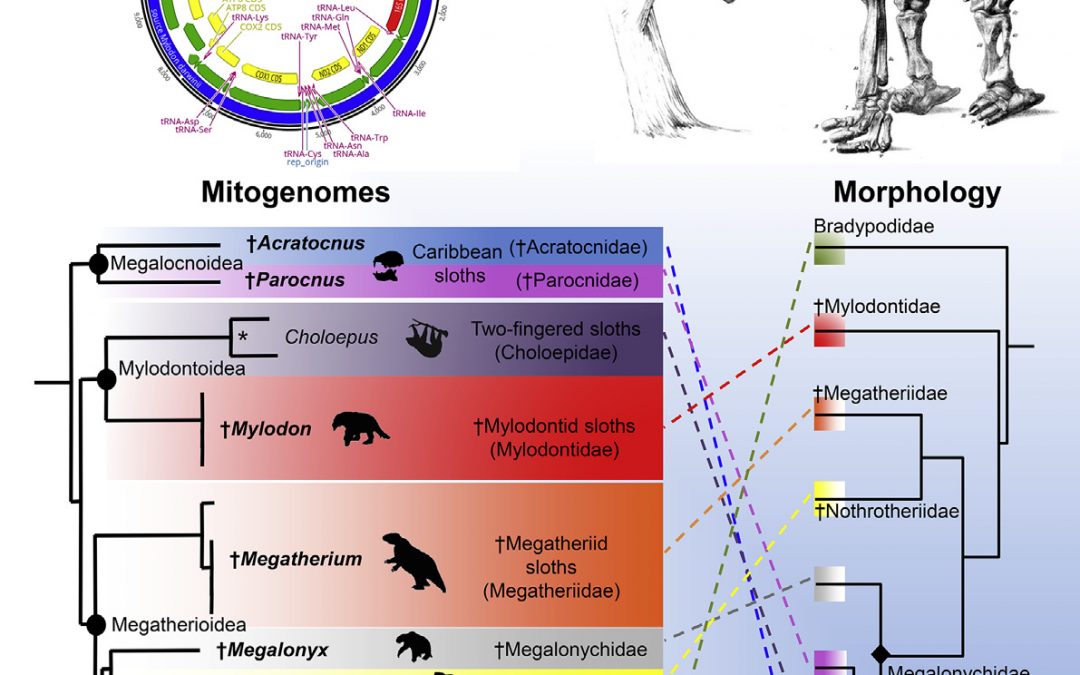

Ancient Mitogenomes Reveal the Evolutionary

History and Biogeography of Sloths

SUMMARYLiving sloths represent two distinct lineages...