Richard S. White, Research Associate

When Europeans began exploring the New World in the 16th-19th centuries, they encountered a wealth of unfamiliar animals and plants. They generally called these animals by some version of the names of animals with which they were familiar in their homelands. Many had close relatives, but some were different enough that deciding what they should be called wasn’t simple. The first explorer to describe what is almost certainly the pronghorn was Pedro de Castañeda, who journaled Coronado’s expedition in 1540, describing them as flocks of goats that were “so fast that they disappeared very quickly.” In 1776 Maraga noted that they were called berrendos, a Spanish word meaning “two-colored”, the same name they have today in Mexico. In 1804 Lewis and Clark saw them somewhere along the Niobrara River and called them “goat-like antelopes.”

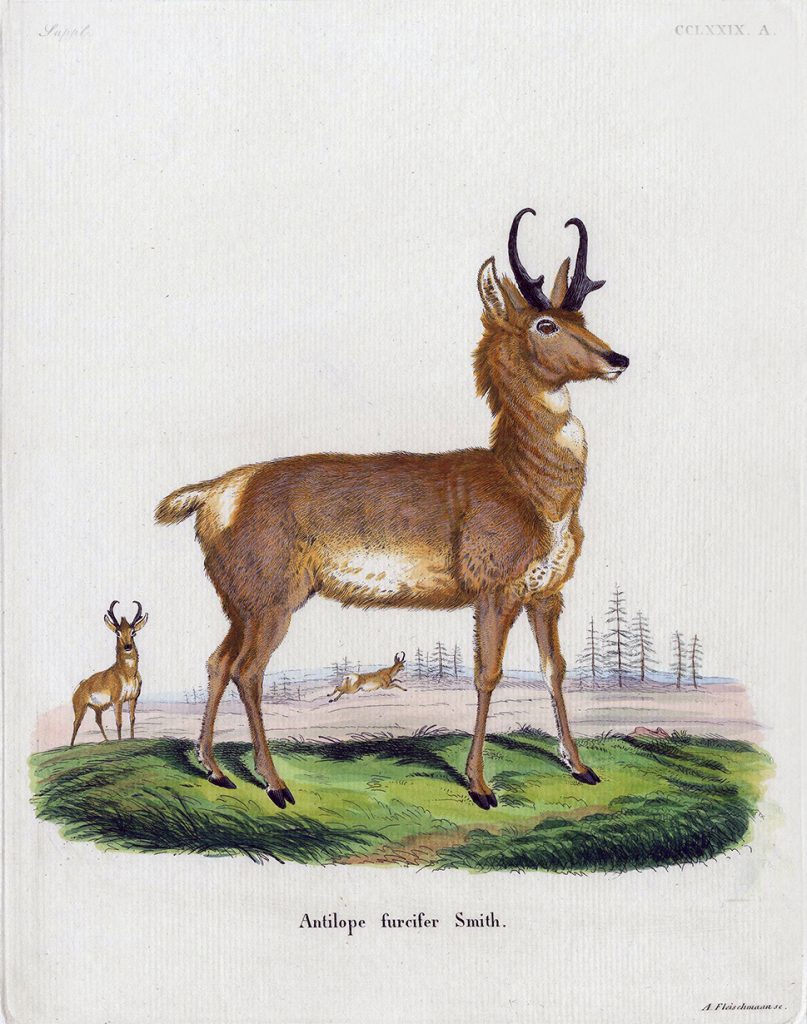

George Ord, who wrote the first comprehensive account of the mammals and birds of western North America, gave them their first scientific name, Antelope americanus, in 1815; he changed that to Antilocapra americana in 1818, its proper scientific name today. Interestingly enough, none of the earliest European explorers provided a drawing of what the pronghorn looked like until Johann Schreber published the first illustration of a pronghorn in 1775, a color lithograph by an unknown artist.

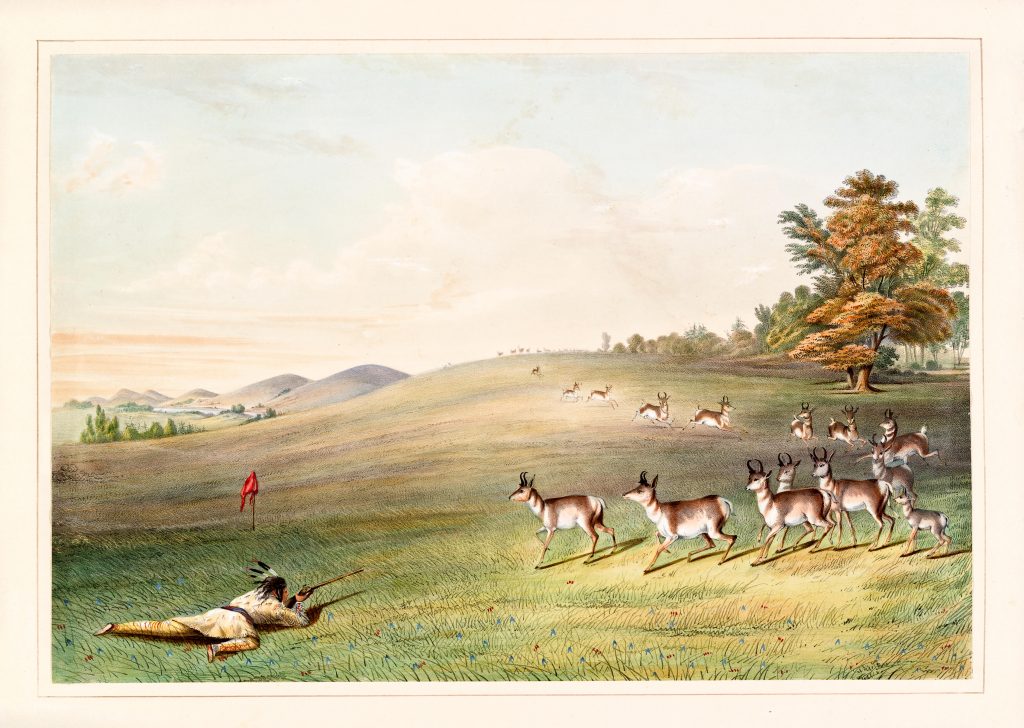

While the Europeans who explored the American West may not have been familiar with the pronghorn, Native Americans certainly knew them well; 330 different names have been recorded from 219 Native American languages. They were an important source of animal protein and were extensively hunted throughout their range. It is to the Native Americans that we owe the first depictions of what pronghorns look like.

The earliest securely dated pronghorn images consist of dozens of ceramic bowls from the Mimbres Culture in New Mexico, with their stylized, but certainly recognizable, pronghorns. Other images in Southwestern rock art may be older but are not securely dated.

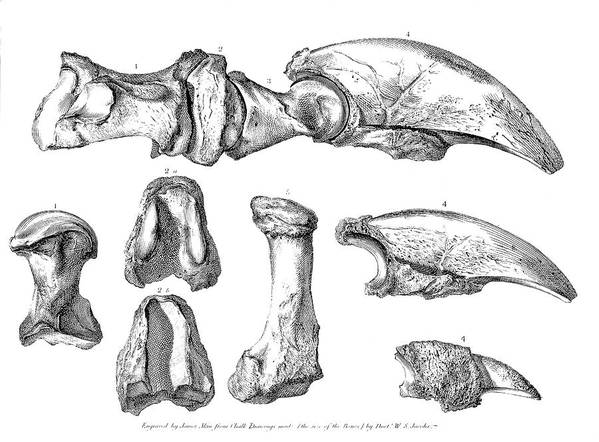

The American Pronghorn was long considered to be endemic, that is, it evolved in North America and had no close relatives in the Old World. The earliest fossil relative of the living pronghorn in North America is about 28 million years old. A wealth of different kinds of pronghorn appeared after that time, with all but one species, the living pronghorn, becoming extinct.

The relationships of the fossil pronghorns have been intensively studied, with the first significant publication in 1937, a 669-page monograph by Childs Frick, son of wealthy industrialist Henry Clay Frick, who devoted his career and his considerable fortune to collecting and describing fossil mammals from the North American Tertiary formations, amassing what is arguably the largest, best-documented collection of such fossils in the world. Unfortunately, his work, while voluminous, was disorganized, often superficial, and lacks the scientific rigor to make it very useful today as anything more than a catalog of the fossils his collecting crews excavated and sent back to him in New York. That superb collection, and its associated data, is Frick’s real scientific legacy.

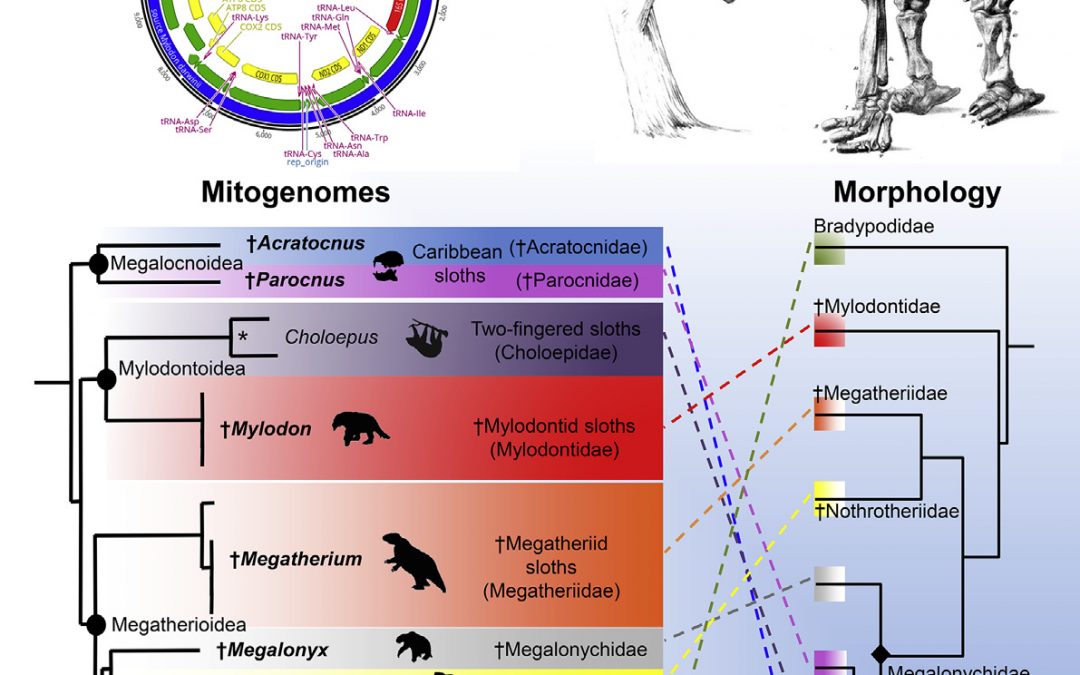

The modern study of pronghorns was ushered in with the 1998 work of Christine Janis and Earl Manning. Based primarily on the cladistic analysis of Manning, they reviewed the entire family of Antilocapridae, providing a useful framework for all further studies. Cladistics is a method of classification of animals and plants according to the proportion of measurable characteristics that they share. Edward Davis updated the phylogeny in his 2007 chapter “Family Antilocapridae” in Prothero and Foss’s “The Evolution of Artiodactyls” volume. Much yet remains to be done to fully understand the evolution and classification of pronghorns. Most of the fossil material needed to do so is in the collections of the American Museum of Natural History into which the Frick collection had been added after the death of Childs Frick in 1965. More collecting is needed in the Oligocene and Eocene formations of Asia to find animals that might have been closely related. There are tantalizing scraps from the Hsanda Gol Formation of Central Mongolia (31-33 million years old), but so far, they consist of only a few teeth.

During the 28 million years of pronghorn evolution in North America, the group developed a wide diversity. Different horn forms, some bizarre, appeared while the body form and dentition remained conservative. Horns resembling those of deer, goats, and antelopes evolved, some with one horn on each side, while others had two or three horns on each side. One lineage, Capromeryx, became dwarfed during the Ice Age. Four different kinds of pronghorn lived during the Ice Age: Stockoceros, Tetrameryx, Capromeryx, and the living pronghorn, Antilocapra. Why the only one of the four to survive the extinctions at the end of the Ice Age should be the modern pronghorn is a mystery currently being investigated by researchers, including those at the Mammoth Site.

Oddly enough, one of the remaining problems is determining just exactly where the living pronghorn fits in. None of the fossil species proposed as most closely related are satisfactory ancestors.

Today, the American Pronghorn is the iconic inhabitant of grassland prairies. It is an important game animal, with populations carefully monitored and managed by state wildlife agencies.

The next time you are in Hot Springs, South Dakota, come visit the exhibit hall where we have a new display about the evolution of the pronghorn.