History and Biogeography of Sloths

SUMMARY

Living sloths represent two distinct lineages of small-sized mammals that independently evolved arboreal-ity from terrestrial ancestors. The six extant species are the survivors of an evolutionary radiation marked by the extinction of large terrestrial forms at the end of the Quaternary. Until now, sloth evolutionary his-tory has mainly been reconstructed from phylogenetic analyses of morphological characters. Here, we used ancient DNA methods to successfully sequence 10 extinct sloth mitogenomes encompassing all major lineages. This includes the iconic continental ground sloths Megatherium, Megalonyx, Mylodon, and Nothrotheriops and the smaller endemic Carib-bean sloths Parocnus and Acratocnus. Phylogenetic analyses identify eight distinct lineages grouped in three well-supported clades, whose interrelationships are markedly incongruent with the currently accepted morphological topology. We show that recently extinct Caribbean sloths have a single origin but comprise two highly divergent lineages that are not directly related to living two-fingered sloths, which instead group with Mylodon. Moreover, living three-fingered sloths do not represent the sister group to all other sloths but are nested within a clade of extinct ground sloths including Megatherium, Megalonyx, and Nothrotheriops. Molecular dating also reveals

that the eight newly recognized sloth families all orig-inated between 36 and 28 million years ago (mya). The early divergence of recently extinct Caribbean sloths around 35 mya is consistent with the debated GAARlandia hypothesis postulating the existence at that time of a biogeographic connection between northern South America and the Greater Antilles. This new molecular phylogeny has major implications for reinterpreting sloth morphological evolution, biogeography, and diversification history.

INTRODUCTION

Sloths (Xenarthra; Folivora) are represented today by six living species, distributed in tropical forests throughout the Neotropics and conventionally placed in two genera: Choloepus, the two-fingered sloths (two species), and Bradypus, the three-fingered sloths (four species). Tree sloths typically weigh 4–8 kg and are strictly arboreal. However, the living species represent only a small fraction of the past Cenozoic diversity of sloths. More than 100 genera of sloths have been systematically described, including the large-bodied species of the Pliocene and Pleisto-cene popularly known as ground sloths of the Ice Age. This includes the giant ground sloth (Megatherium americanum) with an estimated body mass of more than 4,000 kg and Darwin’s ground sloth (Mylodon darwinii), named for Charles Darwin, who collected its first fossil remains. Like their closest xenarthran relatives (anteaters and armadillos), sloths originated in South America and successfully invaded Central and North America prior to the completion of the Isthmus of Panama [1]. Pleistocene North American representative taxa include the Shasta ground sloth (Nothrotheriops shastensis) and Jefferson’s ground sloth (Megalonyx jeffersonii), whose range extended up to Alaska. Late Quaternary ground sloths went extinct ?10,000 years before present (yrbp) as part of the megafaunal extinction that occurred at the end of the latest glaciation [2]. However, sloths also reached a number of Caribbean islands, giving rise to an endemic radiation best known from Quaternary taxa (Megaloc-nus, Neocnus, Acratocnus, and Parocnus)[3] that became extinct only shortly after the appearance of humans in the Greater Antilles ?4,400 yrbp [4]. When and how sloths colonized the West Indies is still disputed. The oldest accepted fossil evidence dates from the early Miocene of Cuba [5], although discoveries in Puerto Rico [6, 7] demonstrate that terrestrial mammals, possibly including sloths, were already in the Greater Antilles by the early Oligocene. These findings would be consistent with the debated GAARlandia (GAAR: Greater Antilles + Aves Ridge) paleobiogeo-graphic hypothesis postulating the existence of a land bridge via the Aves Ridge that would have briefly emerged between 35 and 33 million years ago (mya) and connected northern South America to the Greater Antilles [6].

Read the Full Research Paper Below

Lang Family Dig Building Dedicated

HOT SPRINGS, S.D. – Donations and support from local...

Mammoth Site Awarded Re-Accreditation from the American Alliance of Museums

For Immediate Release Release Date: July 14, 2023...

International Beaver Day

Kelly Lubbers, Bonebed Paleontologist Happy...

A Bone Voyage

“I have been wonderfully lucky, with fossil bones — some of the animals must have been of great dimensions: I am almost sure that many of them are quite new; this is always pleasant, but with the antediluvian animals it is doubly so.” —Letter from Charles Darwin to his sister Caroline, October 1832.

Botany and Bones in Brazil

By Greg McDonald The first discoveries of the ground...

The American Pronghorn and its Ancient Relatives

Richard S. White, Research Associate Antilocapra...

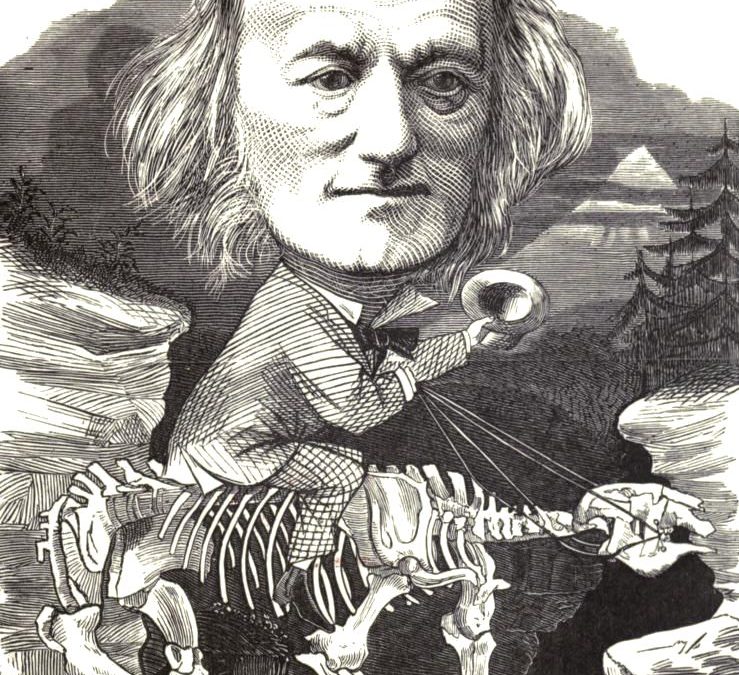

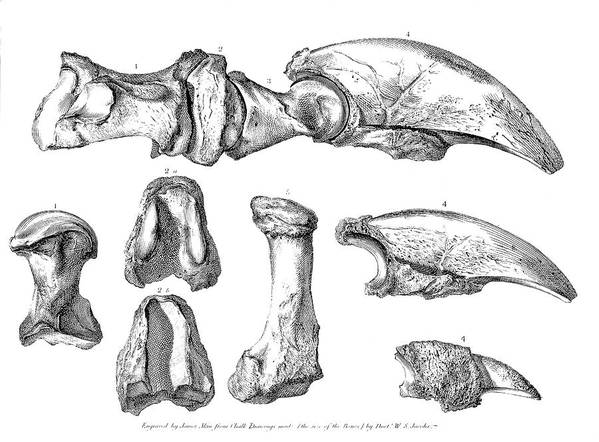

Saltpeter and Sloths

It was not long after Cuvier described the first...

Mammoth Site Researchers Involved In Discovery of New Capybara Fossil Species

HOT SPRINGS, S.D. – Researchers from The Mammoth Site...

The Discovery of Sloths: Strange Animals in a Strange New Land

When you have an animal named after one of the seven...

Proboscideans from US National Park Service Lands

Jim I. Mead, Justin S. Tweet, Vincent L. Santucci,...